Knowing how to write a memoir can be difficult, especially when we’re starting out. In this interview, Writers.com instructor Anya Achtenberg covers the seven essential memoir writing tips—and how to write a memoir in the closely related forms of literary nonfiction and autobiographical fiction.

Below is the full interview audio:

And below is the interview transcribed into Anya’s seven memoir writing tips:

Writing a memoir? Tips to get started

1. Keep an open mind about genre and form

There’s memoir and creative nonfiction, and then there’s fiction that has a deep autobiographical base. And the first thing is not to worry about which of those you’re going to be working in.

You may think it’s memoir, and end up changing to autobiographical fiction. You may be sure you’re going to write a novel, and realize that your own material is coming forward more and more, more than you expected, and it’s very compelling, and there’s a meaning in the midst of it that you’re working to get at. And so you may go over to memoir or creative nonfiction.

So that’s the first thing: you may feel you know what genre you’re working in, and that’s fine, but just to keep one part of yourself open to the possibility that something may change.

2. Use tools from fiction writing to bring forward memory into story

Any work with autobiographical work will be using memory. There are lots of tools, suggestions, writing explorations, and discussions that we use to help bring that material forward, to allow memory to come forward.

Even if you’re definitely writing memoir or creative nonfiction, you’re going to be using tools that fiction writers use. Those tools will help you write your story in a compelling way. There’s a writer, Richard Selzer, who’s a surgeon. He wrote an essay about surgery called “The Knife.” If he wrote about every single time he picked up the scalpel, it would be boring. It would be boring for him to write, and it would not get to the deepest essence of what he’s going for.

And so there’s something, for example, called the representative scene, which we use in fiction and also in memoir. We don’t describe “every morning when we went to school”: we let those mornings come together, so that we see the patterns in those mornings, the depth of meaning in them.

So you use those tools regardless of what kind of story you’re writing, which is one reason why I love to teach these different forms together.

3. Write “the truth as it seems”

Another point I think is important about working with autobiographical material is that we never remember things across an entire life exactly how they happened. So we’re always finding a way to tell the story.

If you’re writing memoir or creative nonfiction, you have a pact not to lie: not to tell great big lies purposefully. Our memories can always be tricky, so it’s hard to say “I’m writing my memoir, and everything in it is absolutely true.” There’s always the caveat as I remember it.

Issues of memory connect to issues of trauma. There’s a wonderful writer who’s a Vietnam vet, Tim O’Brien, who talks about writing the truth as it seems: the truth that the person who lived through that experience has. A war vet who went through trauma can only write the truth as it seemed to him in that traumatic situation.

4. Use imagination within memoir and autobiographical writing

In fiction, of course we’re free to use imagination as much as we feel like. If you’re writing memoir, you can also use imagination, and that can be necessary to get the fuller story.

For instance, you can speculate, and make it clear you’re speculating: “I don’t know where my mother went those nights. Sometimes I think she might have done this, sometimes I think she might have done that.” There’s a whole realm where speculation’s important, not just because you want freedom, but also because if you go back to that child who didn’t know where their mother was, speculation is part of the story: that kid’s going, “Where’s my mom?” So speculation becomes part of the story, even of memoir, and people often don’t realize that they have that whole realm available for them.

5. Develop your narrative voice

One of Anya’s go-to writing a memoir tips starts with your own personal voice. In memoir, in creative nonfiction, and in autobiographical fiction, it’s very important to develop your narrative voice, the voice of your narrator. In everything I teach about story, we do a lot of work on this.

Your narrative voice can make the difference between a collection of things that are not brought together in any particular way, or “Here’s a story, but it’s not very interesting,” and something compelling, interesting, and moving. What moves you into the depth of story—the meaning of it, the richness and specificity of it—is the narrator, that narrative voice.

The narrator is not just a voice floating around who just kind of inhabits the story and tells us what happens. A narrative voice has a very particular vision and personality, perhaps a particular way of using language, a particular sense of humor. Anyone writing memoir, creative nonfiction, or an autobiographically based novel or work of fiction needs to do a lot of work with narrative voice to make that story tell its truth, to organize what you include and what you exclude. That is not just an arbitrary thing, or putting in as much as possible: it has to do with the vision of the narrator. What is important and compelling to them? What details would they notice or stress? What are they trying to hide? What is their personality? Are they a smartass? Are they delicate? That makes a completely different story, and a completely different text, and it lets you shape and be present with autobiographical material, and to bring it forward more than you ever imagined.

6. Use structure in service of story, not vice versa

Finding your narrative voice helps you find your story’s structure. There’s a lot of discussion and dispute about how a story is supposed to be structured, and the idea of a preordained structure. Part of what my courses in this area help people do is to bring forward writing with its own clusters of meaning and connection, and to help them find the structure that is within their story.

You don’t have to beat up your life and your life’s material to fit a certain kind of story structure because some old guy said it’s supposed to do that. The meaning of your life and your story should not be violated by a pre-set structure. That doesn’t mean the story doesn’t have structure, but it means that you and your material work together to find that structure. It’s a deep process of finding the organizational shape of your story.

7. Everything that brings forward your writing is good

If I only had one minute to give someone memoir writing tips, I’d tell them: Everything that brings forward your writing is good. Don’t worry immediately about what it means.

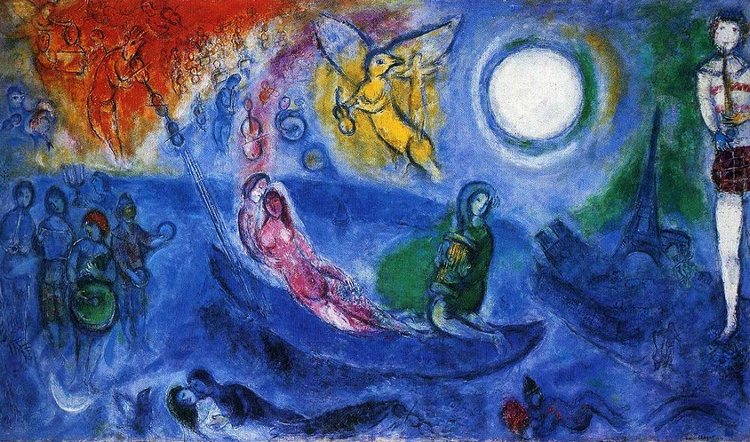

One of my writing goddesses, Toni Morrison, said that first she brings forward the image, and then she figures out what it means. Because she doesn’t predetermine “this, logically, is my story,” but instead allows the material to come forward, when she’s finished with that material, she knows full well what those images are about, and what connects to them. She doesn’t push it around to make them do what she wants them to do.

This is living, vital, creative, associative, powerful material, and we want it to both call forward a lot of work from you, and also deeply respect this content that’s part of you and part of your life. That’s what we do.

You can learn more about Anya and her work at her website, The Disobedient Writer.