When Fanny Kemble, an acclaimed nineteenth-century British actress, marries Pierce Butler, a Philadelphia aristocrat, she is yoked to a philanderer, a liar, and, as she soon learns, a slaver. She must deal with a husband who expects her absolute obedience, as though she were one of his slaves. As an abolitionist, she feels compelled to go down to Georgia, to Butler Plantation, to witness, firsthand, her coerced complicity in this vile institution. An unwanted presence, Fanny soon becomes a force to be reckoned with not only for herself but for her husband’s mistreated slaves.

When Fanny Kemble, an acclaimed nineteenth-century British actress, marries Pierce Butler, a Philadelphia aristocrat, she is yoked to a philanderer, a liar, and, as she soon learns, a slaver. She must deal with a husband who expects her absolute obedience, as though she were one of his slaves. As an abolitionist, she feels compelled to go down to Georgia, to Butler Plantation, to witness, firsthand, her coerced complicity in this vile institution. An unwanted presence, Fanny soon becomes a force to be reckoned with not only for herself but for her husband’s mistreated slaves.

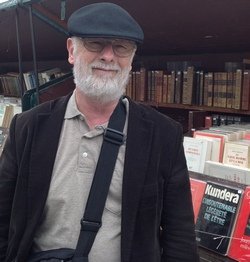

This is the plot of If Winter Comes, the sixth published novel of instructor Jack Smith. I’m particularly excited about this work and how Jack Smith has approached the historical writing process, so I hoped Jack might offer some insights on how he wrote and published this novel.

This is a great interview on the writing and publishing process, as well as the trials of writing historical fiction. Take note from a master of the craft, and read our interview below!

Craft Interview for If Winter Comes

Novels are not screeds, but felt life, and I want my reader to become Fanny just as I have.

1. If Winter Comes follows the American Slavery Era from a British lens. What inspired you to write this work of historical fiction?

I first became interested in Fanny Kemble, an acclaimed Shakespearean actress, when I viewed the film Africans in America, around 20 years ago. I was struck by Fanny’s terrible sense of complicity since her husband, Pierce Butler, was a slaveholder in Georgia. Her painful realization of where her prosperity was coming from really made me want to write a novel about her.

Down in Pierce’s slave plantation, Fanny did as much as she could to relieve the suffering of the slaves. This novel project was on the back burner for a number of years as I worked away at other projects, including my first novel, Hog to Hog, a satirical work, quite unlike the novel that would become my first historical novel.

Jack's Upcoming Courses:

Write Your Novel! The Workshop With Jack

July 3rd, 2024

Get a good start on a novel in just ten weeks, or revise a novel you’ve already written. Free your imagination, move steadily ahead and count the pages!

Writing Autobiographical Fiction

July 17th, 2024

Learn to depart from "what really happened," and write compelling fiction from your own life experiences.

2. In this novel, you’re writing from the lens of a nineteenth-century British aristocratic female. What was your process for researching and writing from such a different perspective?

Once I began to get serious about writing this novel, I started with Fanny Kemble’s Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation: 1838-1839, as well as her American journal. Over the years—about a dozen—I read from her journals plus numerous biographies and historical accounts of the period, books as well as Internet sites. All this was the groundwork.

When I could make use of my research material to become Fanny, and not feel constrained by it, I was writing from her, not about her.

Initially, it was very difficult to get into Fanny’s head and write from her voice and vision. I needed the biographical and historical details, but it was a long time before I could limber up enough to become her—which is what I had to do, just as Flaubert said about Madame Bovary: “Madame Bovary is me.” When I could make use of my research material to become Fanny, and not feel constrained by it, I was writing from her, not about her. She isn’t the real Fanny Kemble, but my fictional creation, though she is certainly based on Fanny Kemble.

3. What do you want the reader to experience through If Winter Comes?

I want the reader to get involved in the emotional and psychological depths of my protagonist, to be there with her as she struggles to gain independence in a miserable marriage to a philanderer, a liar, as well as a slaver, and to root for her as she sets out to do all she can for her husband’s slaves—against her husband’s wishes. Novels are not screeds, but felt life, and I want my reader to become Fanny just as I have.

4. Which authors did you draw inspiration from while writing If Winter Comes? How did they inform or influence the novel?

I read a few antebellum novels like Sue Monk Kidd’s The Invention of Wings and Kathleen Grissom’s The Kitchen House, but mostly Fanny’s journals. Those biographies not only informed me but influenced me to write her story. I found her life fascinating. I do want to emphasize that I’ve departed from the biographical details where necessary—in some cases, rather substantially—so that Fanny, Pierce, and others are all, when it comes down to it, made-up characters, as are the events they’re involved in, though some events closely parallel real life events.

5. Walk me through your novel writing process a bit. Did you plan out this novel from idea to storyboard? Or did you start writing in a more informal way? Was your process here similar to your other novels?

Soon after I got serious about writing this novel, I created my first outline. But it was hard to write from it. I seemed compelled to stick to facts, dates, deeds. In fiction your imagination has to take over; but the research was taking over, so I wasn’t able to get into Fanny’s head yet.

The more deeply I got into my novel, the planning as well as writing, the more I wanted to tell Fanny’s whole story; I didn’t want to leave a thing out. There were so many rich veins of ore to mine. Eventually, though, I realized I absolutely must focus, leaving out material I hated to leave out. I had to decide what was important and what worked to create a good character and a good story—real life doesn’t necessarily make a good story. The ending had to work. It mustn’t be anti-climactic. I would have to devise an ending that was satisfying. This was fiction, after all, not biography.

One of my major problems was writing realism. My fiction had, up to then, been satire and dark humor, and this novel was going to be different—it was straight realism. (Though I did work some dark humor into it, finally.) Until I could find my voice, I just couldn’t write this novel. It didn’t have any soul to it, namely Fanny’s soul. I worked and worked on style, rewriting some scenes probably a hundred times or more. It’s the language that creates the voice; it’s the voice that creates the soul of your character.

It’s the language that creates the voice; it’s the voice that creates the soul of your character.

I loved the research, but the many historical details I found quite challenging—to create verisimilitude. I was dealing with all this even in the last stages, the fine-tuning stage, even the proofing stage, continually checking and re-checking. Novel writing for me, like all writing, is recursive—to the very end.

6. If Winter Comes is your sixth published novel, and I’d love it if you could talk a bit about the publishing process. How do you work with publishers?

I began by trying to market my novel to agents. If you want a commercial press, you must be represented by an agent. I soon learned that commercial publication wasn’t right for this novel. I suppose it didn’t look like a money-maker. That’s the bottom-line for commercial publishers. It’s got to sell; it’s got to be profitable.

I decided that wasn’t as important to me as having my work published by a reputable independent press. Except for Hog to Hog, which won the George Garrett Fiction Prize and was published by the Texas Review Press, my novels have been published by Serving House Books, which I admire for the quality work they’re putting out plus the notable writers they’re publishing. I wanted this new novel to be included with four of my other novels on their list; I submitted it, and it was accepted. It’s found a good home.

Read If Winter Comes by Jack Smith today!

Jack’s novel can be found at the following booksellers: