The simile, the metaphor, and the analogy are some of the most common literary devices, giving writers the tools to compare different ideas, concepts, and experiences. Yet, because these three devices are all comparisons, it can be difficult to keep track of which device means which. What is a simile vs. metaphor vs. analogy?

Whether you write poetry, fiction, or nonfiction, your writing will drastically improve with the use of these literary devices. Understanding the conundrum of simile vs. metaphor will sharpen the impact of your words, while developing a proper analogy will help you develop a much stronger argument.

This article aims to give you mastery over these essential literary devices, with definitions, examples, and writing exercises for each device. With a deep understanding of simile vs. metaphor vs. analogy, your writing will take on new depth and clarity. Let’s dive in!

Simile vs Metaphor vs Analogy: Contents

Simile Definition: The Indirect Comparison

The words “simile” and “similar” come from the same root, and that’s exactly what a simile is: a comparison of similar things.

Specifically, a simile compares two or more items using “like,” “as,” or another comparative preposition. Also known as an “indirect comparison,” the simile allows writers to explore the many facets of complex ideas.

A simile compares two or more items using “like,” “as,” or another comparative preposition.

Take these three simile examples:

- My cat is as loud as Yankee Stadium.

- My cat is soft and fluffy, like a teddy bear.

- My cat destroys furniture the way bulldozers destroy buildings.

These similes offer very different descriptions, yet coexist quite peacefully in my cat—who is, in fact, loud and soft and destructive.

Simile Examples

Here are some more simile examples, all of which come from published works of literature.

- “In the eastern sky there was a yellow patch like a rug laid for the feet of the coming sun” — The Red Badge of Courage, by Stephen Crane

By portraying the color of the horizon like a rug, this simile makes the sun seem regal and majestic. This is also a great example of “show, don’t tell” writing, because we know the sun is rising without being told it’s dawn.

- “The world will burst like an intestine in the sun” — “Passengers” by Denis Johnson

What an uncomfortable image! Would you believe this simile is the first line of a sonnet? Comparing the world to a “burst intestine” adds a visceral quality to the poem, as it treats the world as a living organism in peril. Additionally, the words “burst” and “intestine” have a slimy sound to them, making this simile both disturbing and intriguing.

- “You lived your life like a candle in the wind” — “Candle in the Wind” by Elton John (lyrics by Bernie Taupin)

This simile is deceptively simple because it paints a complex image. How does a candle react to the wind? Sometimes it flickers, sometimes it stands even taller, and sometimes it wanes to an ember, waiting for the weather to pass.

Bernie Taupin, Elton John’s co-songwriter, wrote the lyrics for “Candle in the Wind” to commemorate the life of Marilyn Monroe, but although the song is specific to one person, the simile could apply to anyone, demonstrating the simple power of this literary device.

Simile Writing Exercises

It’s your turn to write some similes! A simile should be concise yet expressive, stimulating the reader’s mind without “spoon feeding” a certain interpretation. As you work through these exercises, keep your simile examples descriptive, yet open-ended.

1. Simile Comparison Lists

On a blank piece of paper, create two lists, with each list containing 6 items.

In one list, jot down six different abstract nouns. An abstract noun is something that doesn’t have a physical presence: words like “love,” “justice,” “anger,” and “envy” are all abstract. Words that end in -ism are usually abstract, too, like “solipsism,” “capitalism,” and “antidisestablishmentarianism.”

In the other list, jot down six different concrete nouns. These are nouns that you can touch or observe—so, even though you can’t touch the planet Neptune, it’s still concrete and observable. Try to use nouns that are in most peoples’ vocabularies: the reader is much more likely to know what a basketball is than what a chatelaine is.

For reference, your list might look like this:

| Abstract Noun | Concrete Noun |

| Love | Bluejay |

| Justice | Leather wallet |

| Anger | Basketball |

| Envy | Pencil sharpener |

| Peace | Balloon |

| Democracy | The planet Mercury |

Now, connect each abstract noun to a random concrete noun. Try not to be too intentional about which nouns you connect: the point is to compare two different items at random.

Once you’ve connected your two lists, it’s time to write! You’re going to write six similes, one for each pair of nouns. Your similes will use the concrete noun to describe the abstract noun, offering a deeper understanding of that abstract noun.

For example, I might connect the words “anger” and “pencil sharpener.” The goal is to offer a deeper understanding of “anger” through visual description, so I might write the following simile:

- “Anger, like a pencil sharpener, made my words precise while grinding me to dust.”

Write a simile for every noun pair in your list, and see what you come up with! This exercise might spark an idea for a poem, give you a powerful line for a short story, or simply juice your creativity.

2. Simile Poetry

Something wonderful about similes is their versatility. The same object can be described through a series of similes, each simile building off of each other to build a full and complex image.

There’s even such a thing as simile poetry, which is exactly what it sounds like: a poem consisting of similes. Read the poem Surety by Jane Huffman, which abounds with great simile examples.

The goal of this exercise is to write your own simile poem. We’ll follow a simple four step process to do this.

First, select an object or concept that you want to write about. You have free range here: select something as trivial as a spoon, as complicated as time travel, or as abstract as godhood.

Second, generate a list of nouns. Set a timer for 2 minutes and write down as many nouns as you can think of. Try to stick to concrete nouns, as abstract nouns will prove harder to write with.

Third, write some similes! Compare the topic of your poem to each of the nouns you just listed. You don’t have to use every noun, as there might be nouns in your list that have nothing in common with your topic. The goal is to create strong, impactful similes, each of which demonstrate a different facet of the complex idea you’re writing about.

Fourth, assemble your poem. You can write a poem entirely out of similes the way Jane Huffman did, or you can use these similes strategically, like how Kyle Dargan uses the simile to write his ghazal Points of Contact.

Metaphor Definition: The Direct Comparison

The word “metaphor” comes directly from the Greek word metaphora, “a transfer.” That’s exactly what metaphors do: they transfer identities, altering the reader’s understanding of the nature of something.

A metaphor is a statement in which two items, often unrelated, are treated as the same thing. Also known as a “direct comparison,” metaphors can create powerful imagery and description, deepening the meaning of objects and ideas.

A metaphor is a statement in which two things, often unrelated, are treated as the same thing.

Rather than using “like” or “as” like similes do, metaphors are statements of being, often using words like “is,” “are,” and “became” to make a comparison. Metaphors can also make a comparison without using “being verbs” or other comparison words. Take these three metaphor examples, each of which draw a portrait without using excessive language:

- The grandfather clock is king of the family room furniture.

- The grandfather clock became a death knell for her childhood.

- The grandfather clock had the face of an estranged lover.

Let’s address what each of these metaphors accomplish. The first metaphor shows us the clock’s size and importance; the second metaphor shows us the clock’s ominous presence, focusing on its sound; the third metaphor treats the clock as forlorn and solitary.

In other words, each of these metaphors express the relevance of the grandfather clock without stating it explicitly. Such is the beauty of metaphors: the ability to tell a story through proximity.

Before we offer some more metaphor examples, we need to discuss two important facets of metaphor writing, especially as they relate to simile vs. metaphor.

First, metaphors rely on the suspension of disbelief—in other words, the reader knows they’re being lied to, but accepts it anyway. Obviously, a clock cannot be a king, nor can it be a death knell or a lover… it’s a clock, after all. Nonetheless, the reader accepts what is being told to them because they trust that the metaphor, and what it conveys, is relevant to the text. Metaphors can be imaginative—magical, even!—but they must be relevant.

The metaphor is more “complete” than the simile.

Second, the metaphor is much more “complete” than the simile. If I was actually writing about a grandfather clock, I would only choose one metaphor and stick with it. Multiple metaphors will contradict each other because they’re creating different statements of being. The reader will inevitably wonder if the clock is actually a king, a death knell, or neither, and this thought process will end up disrupting the reader’s suspension of disbelief. This type of writing is known as a mixed metaphor.

Now, let’s see some more metaphor examples!

Metaphor Examples

The following metaphor examples all come from published works of literature.

- “Whatever causes night in our souls may leave stars.” —Ninety-Three by Victor Hugo

Sometimes, the simplest metaphors carry the most complex meanings. The premise of this direct comparison is easy to understand: the things that trouble us now may strengthen us later. At the very least, those stars are twinkles of wisdom that we gain from life experience, illuminating our paths forward, if dimly.

Yet, the operative word in this metaphor is “may.” The things that trouble us might strengthen us, but they might also create an eternal dusk. And, even with starshine, our souls can very much be blanketed by night.

What emerges from this metaphor is a bittersweet rumination on life and its many perils. Accruing wisdom is always a choice, but faith in the light is vital for anyone to push forward.

- But, look, the morn, in russet mantle clad,

Walks o’er the dew of yon high eastern hill. —Hamlet by William Shakespeare

This metaphor is a form of personification, a literary device in which nonhuman objects are given humanlike qualities. Specifically, Shakespeare is comparing the sunrise to that of a person, dressed in “russet” red, walking up a hill.

It’s a simple and beautiful comparison. Instead of saying “the sunrise is red,” Shakespeare personifies the dawn itself, showing us its russet color, its slow ascent, and the morning dew that flecks each blade of grass.

- “I’d like to start

a bonfire in my heart

but today there’s just

a stone; last night,

a whirlwind; before,

a broken mirror.” —”Hope Poems” by Jill Robbins

The metaphor here accomplishes several things, but first, we should note that there are several different metaphors here. Every metaphor has two components: the subject, and the thing that subject is being compared to. (These are known as the “tenor” and the “vehicle,” which we’ll explain in the next section.)

So, the subject (tenor) of this metaphor is the speaker’s heart, and the comparisons (vehicles) are a bonfire, a stone, a whirlwind, and a broken mirror.

Each of these objects describe something different about the speaker’s heart. She would like her heart to be a bonfire—a symbol of passion and livelihood. Instead, her heart is a series of objects that cannot catch fire, with each object symbolic of something else. A stone might symbolize heavy and immovable emotions; a whirlwind might represent the speaker’s capricious feelings; a broken mirror might reflect the speaker’s fragmented sense of self.

“But wait! Isn’t that a mixed metaphor?” Yes—but it’s a mixed metaphor that works. The series of incongruent symbols gives the reader a window into the speaker’s heart. By comparing each symbol to the speaker’s desired “bonfire heart,” the reader recognizes the many emotions preserved in each image.

Wielding Metaphor Effectively

Aristotle said:

“The greatest thing by far is to be a master of metaphor. It is the one thing that cannot be learned from others; it is also a sign of genius, since a good metaphor implies an eye for resemblance.” (“De Poetica,” 322 B.C.)

So how can you be a genius?

In a metaphor, one thing is likened to another. Vivid metaphors are considered a mark of good writing. Since a metaphor disregards logic—an object cannot be something else and be itself at the same time—some consider it “superior” to the simile (though there are plenty of superior similes out there).

“Bear in mind

That death is a drum

Beating for ever

Till the last worms come

To answer its call.” From “Drum” by Langston Hughes

“No man is an island.” John Donne

“Her face is common property.” From “The Bloody Chamber” by Angela Carter

Good metaphors can become, if they grow to be well known, clichés. (Clichés are “dead metaphors.”) Clichés dull your writing. They become almost invisible to the reader. How do you know your metaphor is a cliché? Other than being well read, you can acquaint yourself with lists from a number of books or check Web sites like Cliché Finder.

Another “bad” metaphor is one that is “mixed.” In a mixed metaphor, the parts of the comparison don’t match. They can be funny, but you don’t want them popping up in your serious writing. Examples of mixed metaphors include:

“It’s deja vu all over again.”

“The flood of students flew out the doors.”

“The insult cut her like a knife; it froze her in mid-sentence.”

There’s also a danger in using metaphor badly and not even realizing we are using metaphors. Jack Lynch, in his “Guide to Grammar and Style” cites this “more or less realistic example of business writing”:

We were swamped with a shocking barrage of work, and the extra burden had a clear impact on our workflow.

“Let’s count the metaphors,” writes Lynch, “we have images of a marsh (swamped), electrocution or striking (shocking), a military assault (barrage), weight (burden), translucency (clear), a physical impression (impact), and a river (flow), all in a mere twenty words. If you can summon up a coherent mental image including all these elements, your imagination’s far superior to mine.”

Lynch then gives a real example from “The New York Times” (11 June 2001):

Over all, many experts conclude, advanced climate research in the United States is fragmented among an alphabet soup of agencies, strained by inadequate computing power and starved for the basic measurements of real-world conditions that are needed to improve simulations.

Lynch: “Let’s see: research is fragmented among soup (among?); it is strained (you can strain soup, I suppose, but I’m unsure how to strain research); and it is starved — not enough soup, I suppose. Or maybe the soup has been strained too thoroughly, leaving people hungry. I dunno.

The moral of the story: pay attention to the literal meaning of figures of speech and your writing will come alive.”

Using metaphors is much more than writing “something is something else.” Using a sustained metaphor that is neither over-extended nor mixed can be effective:

We dived into the debate, sank our serrated teeth into their arguments, tore their ideas into bloody shreds, and then swam away to digest our prey

Use metaphors:

- As verbs: The song ignited his lust but snuffed out her interest.

- As adjectives and adverbs: Her carnivorous brush ate up the canvas.

- As prepositional phrases: The old man considered the scene with a blue-white vulture’s eye.

- As appositives or modifiers: On the stairs he stood, a gawking scarecrow.

Simile vs. Metaphor Examples

What is the difference between a simile and a metaphor? There are a few key traits that separate simile vs. metaphor, and understanding them will help you decide which device to use in your work.

Let’s look at the key differences between simile vs. metaphor, and how these differences affect the meaning of each device.

Simile vs. Metaphor: Comparison Words

A simile will always use a comparison word. The most common of these comparison words are “like” and “as,” but there are other ways of denoting comparison, too. The following statements mean virtually the same thing, but use slightly different terms of comparison:

- The elephant sat still, like a statue.

- The elephant sat as still as a statue.

- The elephant sat still the way statues do.

Metaphors, on the other hand, rely on various forms of the verb “to be”—if they use a comparison word at all. Metaphors can also be implied through punctuation and word choice. All of the following are proper constructions for the metaphor:

- The elephant was a statue amongst the trees.

- The elephant had petrified at the sight of the tiger; a statue of instinct.

- The elephant: a marble statue.

You could even make the noun “marble” a verb, though some traditionalist writers dislike the grammar behind this. Nonetheless, “the elephant was marbled at the sight of the tiger” offers a unique image.

Simile vs. Metaphor: Differences of Intensity

When a simile compares two or more items, each item retains their individual meanings. For example, if I said “this pancake is as thick as a Dostoevsky novel,” you can visualize the thickness of both items while still imagining two different objects, the pancake and the book. The simile is humorous while still being descriptive.

With metaphors, the object of comparison takes on a different image. If I said “this pancake is a Dostoevsky novel,” you would envision a pancake about 1,000 pages thick. Sounds delicious!

Here’s a metaphor and a simile side-by-side. Take note of how your mental image differs between these two sentences.

- The little boy clings to his mother like ivy clings to a tree.

- He was an ivy growing up his mother’s legs.

Simile vs. Metaphor: Degree of Magic

Yes, magic! Because metaphors are statements of being (whereas similes are statements of likeness), a metaphor can rely on visual descriptions that aren’t bound by the laws of logic. An elephant can be marble, a boy can be ivy, and my cat is (and always will be) a bulldozer.

Similes, by contrast, cannot make statements quite as “magical” in nature. While you might make comparisons to mystical items with a simile—“she waved her flag like a magic wand”—there are still two distinct objects at the end of the sentence, not one magically combined idea.

The Extended Metaphor

As we’ve discussed, it is much harder to describe one thing using multiple metaphors. This will inevitably result in a mixed metaphor, which, unless very tactfully written, will confuse the reader instead of enlighten them.

However, another device you can put in your literary toolbox is the extended metaphor. Sometimes synonymous with the literary device conceit, the extended metaphor allows you to explore the implications of the metaphor you just wrote.

The extended metaphor allows you to explore the implications of the metaphor you just wrote.

Let’s start with a simple metaphor:

- Her heart splashed on the asphalt alongside the rain.

The comparison here is easy to understand, and in fact, this metaphor could stand on its own quite easily. But it can also be expanded to say more about the life cycle of a broken heart.

Extended metaphors exist in both prose and poetry. For now, let’s use prose.

- Her heart splashed on the asphalt alongside the rain. Imagine: a torrent you just can’t quench, eddies of water and heartache iridescing towards the drain pipes. When does the feeling quit gushing through sewage systems and underground rivers? When does the water simply calm down? The heart, it sublimates; the heart, it fizzles and gas-ifies and clouds. Whoever said love is eternal was lying: love is a rain cycle. Our hearts, unstudied weather patterns—precipitating.

For examples of extended metaphor in literature, take a look at these poems.

- Hope is the thing with feathers by Emily Dickinson

- Landscape with Fruit Rot and Millipede by Richard Siken

- Habitation by Margaret Atwood

Metaphor Writing Exercises

Ready to try your hand at the metaphor? These two exercises will help you write sharp, polished direct comparisons.

1. Very-Extended Metaphors

To begin this writing exercise, simply come up with two concrete nouns. You will compare one noun to the other, so try to keep your nouns unrelated to each other, so that you come up with more striking language. For example, don’t use “apples and oranges”, but “elephants and statues” will be perfectly different from each other.

Once you have two concrete nouns, set a timer for 10 minutes.

When the timer starts, write down all of the ways that Noun 1 can be Noun 2. Just jot your ideas down; don’t try to write anything “polished.” For example, an elephant is a statue because elephants can stand perfectly still, some are creamy white, both elephants and statues pose, etc.

When the timer stops, go over everything you wrote down. Examine the different reasons that Noun 1 is Noun 2, and start weaving sentences together to build an extended metaphor. Let each comparison have its own sentence, building an argument through metaphor. Be visual with your description: show the reader how Noun 1 is the same thing as Noun 2. When you’ve woven these ideas together, you’ll have an extended metaphor, which could become part of a poem or prose piece.

2. Opposites Attract, Metaphorically

For this metaphor exercise, think of two concrete nouns that are either opposites or near-opposites.

For example, “trees” and “factories” can be considered near-opposites. One is natural and produces oxygen, the other is man-made and produces carbon dioxide.

How can a tree be a factory? How can a factory be a tree? These questions are best answered in metaphor.

Write a metaphor using the two opposing nouns you chose, and explain why Noun 1 is Noun 2. The goal is to surprise the reader with a comparison they didn’t expect. This type of writing, when a metaphor joins two unalike or unexpected things, is known as a “conceit.”

Analogy Definition: The Argumentative Comparison

The word “analogy” comes from the Greek, roughly translated to mean “proportional.” Analogies argue that two seemingly different items are “proportional” and, in doing so, build an argument about a larger issue. An analogy might not be the central device of your writing, but analogies can contribute much-needed perspective to an argument, appealing to the reader’s sense of logic.

Analogies argue that two seemingly different items are “proportional” and, in doing so, build an argument about a larger issue.

An analogy has two purposes:

- The identification of a shared relationship, and/or

- The use of something familiar to describe something unfamiliar.

This will make sense with some analogy examples. Let’s start with a simple one:

- Finding a new species of fish is like finding a needle in a haystack.

This analogy identifies a shared relationship between two things: namely, that finding both objects is difficult. Additionally, it uses a familiar phrase—“like a needle in a haystack”—to describe something that the reader might not know about.

Additionally, this sentence structure “A is to B” is common for analogies. You might also see the construction “A is to B as C is to D.”

An analogy can take the form of a simile or metaphor.

Finally, you might be wondering: Isn’t that analogy also a simile? And the answer is: Yes! An analogy can take the form of a simile or metaphor, which is why identifying one from the other can be a bit tricky. In a bit, we’ll discuss the differences between simile vs. metaphor vs. analogy. But first, let’s look at more analogy examples.

Analogy Examples

All of these analogy examples come from published works of literature. In our analysis, we’ll examine what makes each of these analogies distinct from similes and metaphors.

- “That which we call a rose / By any other name would smell as sweet” —Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare

Shakespeare is negating the idea of nominative determinism—the idea that the name of something changes its essential characteristics. The idea of a “sweet smelling rose” is familiar to the reader, and by modifying this idea to call the rose a nameless flower, Shakespeare suggests that the name “rose” has no effect on the rose’s smell.

In Romeo and Juliet, Juliet says this line as part of a larger argument: that her status as a Capulet does not change his love for her, even though he is a Montague. This rejection of family history for the sake of love is central to the play’s tragedy.

- An author who expects results from a first novel is in a position similar to that of a man who drops a rose petal down the Grand Canyon of Arizona and listens for the echo. —Cocktail Time by P. G. Wodehouse

Although his advice is a bit pessimistic, P. G. Wodehouse illustrates his point with a strong analogy. A rose petal will never create an echo, and even if it could, the Grand Canyon is far too deep for anyone to hear it.

Similarly, an author’s first novel probably won’t find resounding success, and even if it does, it will not change the literary landscape on its own. An author needs to put out consequent novels to have a much larger impact—to throw a boulder down the Grand Canyon and hear its echo, metaphorically.

In this analogy, the familiar idea is an echoless rose petal, and the new idea is an author publishing their first book. This analogy could be rewritten in the following way: “a rose petal echoes the way an author’s first book impacts the literary world.”

- As cold water is to a thirsty soul,

So is good news from a far country. —Proverbs 25:25

The analogy here is clear and simple: water quenches a parched throat the way good news quenches the soul. The reader is naturally familiar with the feeling of a quenched thirst, making it much easier to understand the sense of relief begat by good news—especially if you’re worried about bad news.

This analogy has a sentence structure common to analogies: “A is to B as C is to D.”

Analogy Writing Exercises

Ready to write your own analogy examples? These two exercises will jumpstart your creativity.

1. Start With a Simile

As you’ve seen in the above analogy examples, many analogies can also be characterized as similes. For this exercise, we’re going to start with similes.

Just as we did in the first simile writing exercise, we’re going to create two lists: a list of concrete nouns, and a list of abstract nouns.

Follow the instructions from our first writing exercise for similes, and when you’ve generated a list of similes, we’re going to turn them into analogies.

How do you turn a simile into an analogy? An analogy has two parts: information that’s familiar to the reader, and information that’s new to the reader.

Let’s say you wrote down the line “his car horn sounds like an electric goose.” The electric goose is familiar to the reader: they can imagine that sound in their head. “His car horn” is not familiar, because the reader hasn’t heard this particular car horn before.

The best way to create an analogy from a simile is to use parallel structure, which means both parts of the analogy are constructed the same. Both the horn and the goose “honks,” which makes “honking” the piece of information most familiar to the reader. If we use parallel structure and rely on common information, we can turn the simile into the following analogy:

“He honks his horn like a goose honks at strangers.”

It’s that simple! Of course, whatever analogies you write, you may decide to expand on them more. Analogies can be arguments on their own, and they can also tie into a larger thesis or idea. However, an analogy should be self-explanatory: the reader should not need additional information to understand it.

2. A is to B as C is to D

All you need for this writing exercise is five words: one verb and two pairs of concrete nouns.

Come up with these words however you like. Use a word generator, create a list, flip to a random page in the dictionary, etc. The only requirement is that two of your four nouns can do the verb. (A dolphin can swim, but it can’t type on a keyboard, for example.)

Your list might look like this:

- Verb: Coddle

- Noun Pairs: mother and son, artist and easel

Once you have these words selected, you have everything you need to write an analogy. Your next step is to put them in the sentence structure “A is to B as C is to D.”

So, for the words I randomly selected, my analogy could read like this: “a mother coddles her son the way an insecure artist coddles his easel.”

And there, I have an analogy! If I wanted to, I could write more about how an artist should let go of micromanaging the canvas, allowing art to develop naturally through the artistic process. However, my analogy makes this argument on its own, which a proper analogy should do.

Side by Side: Simile vs. Metaphor vs. Analogy

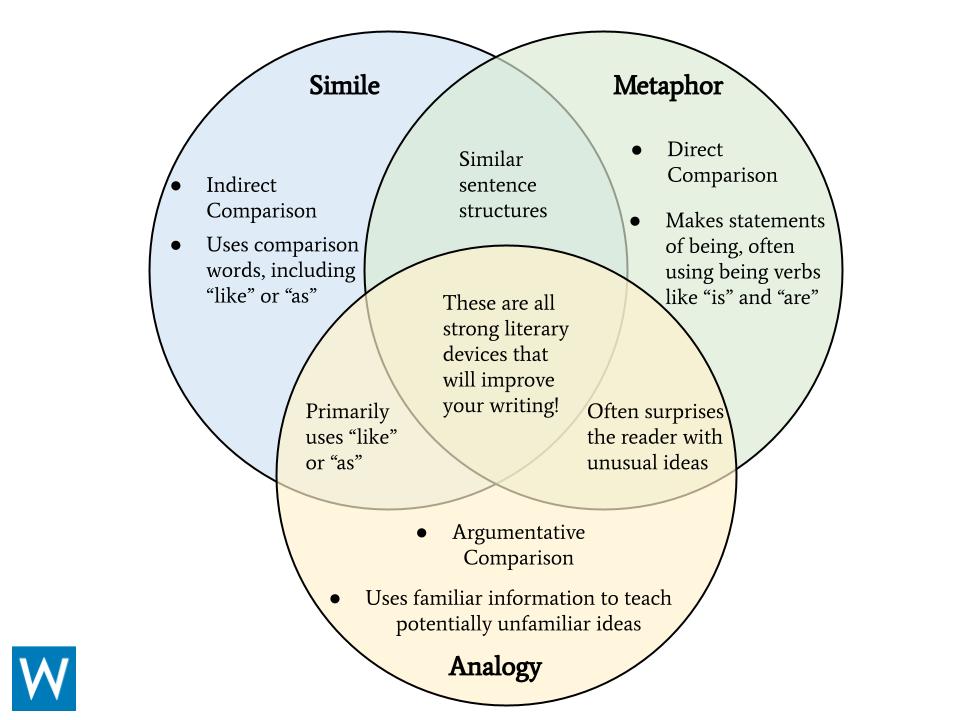

What do similes, metaphors, and analogies have in common, and how do they differ? We’ve summarized this at the following Venn Diagram comparing simile vs. metaphor vs. analogy.

Simile vs. Metaphor vs. Analogy Venn Diagram

Explore More Literary Devices at Writers.com!

Want to sharpen your language with interesting similes, metaphors, and analogies? The resources at Writers.com can help! Our online writing courses can help you learn the tools of writing and finish your works-in-progress. You can also follow our Instagram and join our Facebook group for weekly writing tips and our one-of-a-kind writing community. We hope to see you there!

Thanks, Sean. I’m sure this will be helpful for many writers. I’m sharing on Facebook… and on Twitter.

Thank you so much, Kathy!

Sean,

This section was very informative.Could you clarify my doubt?.In the poem Amanda by Robin Klein..

(I am an orphan, roaming the street.

I pattern soft dust with my hushed, bare feet.

The silence is golden, the freedom is sweet.)

I am an orphan is stated as a metaphor. A comparison is made between her and an orphan. From what I’ve understood it’s not one as orphan is not an inanimate object.PLease clarify my doubt.

Thanks

Regards

Sanzie

Hi Sanzie,

Thanks for your question! Yes, “I am an orphan” is absolutely a metaphor here. Our article mostly sticks to inanimate objects because metaphors with human identities can be tricky to navigate. That said, anything that is a noun can be used in a metaphor. Saying “the grandfather clock is king of the furniture” is also a metaphor using a human identity.

I hope this adds some clarity!

Elton John didn’t write ‘Candle in the Wind’ – that was lyricist Bernie Taupin’s work.

Hi Nick,

Thank you for this correction! I’ve updated the article accordingly.

Warmest,

Sean

This was super helpful! The most descriptive explanation I have found. Thank you!

Thanks, this is helpful

Well explained even to my understanding

Great impact!

This article is refreshing, like a tall cold lemonade on a scorchingly hot day.