The plot of a story defines the sequence of events that propels the reader from beginning to end. Storytellers have experimented with the plot of a story since the dawn of literature. No matter what genre you write, understanding the possibilities of plot structure, as well as the different types of plot, will help bring your stories to life.

So, what is plot? Is there a difference between plot vs. story? What plot devices can you use to surprise the reader? And how does plot relate to the story itself?

In this article, we go over the elements of plot, different plot structures to use in your work, and the many possibilities of narrative structuring.

But first, what is the plot of a story? Let’s investigate in detail.

Contents

Plot Definition: What is the Plot of a Story?

The plot of a story is the sequence of events that shape a broader narrative, with every event causing or affecting each other. In other words, story plot is a series of causes-and-effects which shape the story as a whole.

What is plot?: A series of causes-and-effects which shape the story as a whole.

Plot is not merely a story summary: it must include causation. The novelist E. M. Forster sums it up perfectly:

“The king died and then the queen died is a story. The king died, and then the queen died of grief, is a plot.” —E. M. Forster

In other words, the premise doesn’t become a plot until the words “of grief” adds causality. Without including “of grief” in the sentence, the queen could have died for any number of reasons, like assassination or suicide. Grief not only provides plot structure to the story, it also introduces what the story’s theme might be.

Elements of Plot

The plot of a story must include the following elements:

- Causation: one event causes another, and that cause-and-effect unleashes a whole chain of plot points which formulate the story.

- Characters: stories are about people, so a plot must introduce the main players of the plot.

- Conflict: a plot must involve people with competing interests or internal conflicts, because without conflict, there is no story or themes.

Combining these elements of plot creates the structure of the story itself. Let’s take a look at those plot structures now, because there are many different ways to organize the story’s events.

Plot is people. Human emotions and desires founded on the realities of life, working at cross purposes, getting hotter and fiercer as they strike against each other until finally there’s an explosion—that’s Plot. —Leigh Brackett

Some Common Plot Structures

There are many ways to develop the plot of a story, and writers have been experimenting with plot structures for millennia. Consider the following structures as you attempt to write your own stories, as they may help you find a solution to the problems you encounter in your story writing.

Plot Structures: Aristotle’s Story Triangle

The oldest recorded discussion of plot structures comes from Aristotle’s Poetics (circa 335 B.C.). In Poetics, Aristotle represents the plot of a story as a narrative triangle, suggesting that stories provide linear narratives that resolve certain conflicts in three parts: a beginning, middle, and end.

To Aristotle, the beginning should exist independent of any prior events: it should be a self-sustaining unit of the story without prompting the reader to ask “why?” or “how?” The middle should be a logical continuation of the events from the beginning, expanding upon the story’s conflicts and tragedies. Finally, the end should provide a neat resolution, without suggesting further events.

Obviously, many stories complicate this basic plot triangle, and it lacks some of the finer details of plot structure. One way that Aristotle has been developed further is through Freytag’s Pyramid.

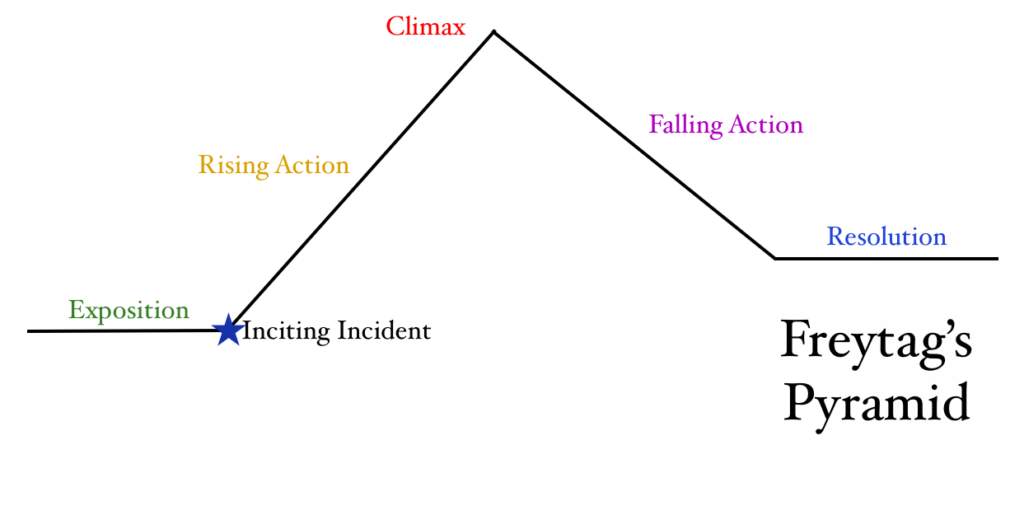

Plot Structures: Freytag’s Pyramid

Freytag’s Pyramid builds upon Aristotle’s Poetics by expanding the structural elements of plot. This pyramid consists of five discrete parts:

- Exposition: The beginning of the story, introducing main characters, settings, themes, and the author’s own style.

- Rising Action: This begins after the inciting incident, which is the event that kicks off the story’s main conflict. Rising Action follows the cause-and-effect plot points once the main conflict is established.

- Climax: The moment in which the story’s conflict peaks, and we learn the fate of the main characters.

- Falling Action: The main characters react to and contend with the Climax, processing what it means for their lives and futures.

- Denouement: The end of the story, wrapping up any loose ends that haven’t been wrapped up in the Falling Action. Some Denouements are open ended.

For more on Freytag’s Pyramid, check out our article. https://writers.com/freytags-pyramid

Plot Structures: Nigel Watts’ 8 Point Arc

A further expansion of Freytag’s Pyramid, the 8 Point Arc is Nigel Watts’ contribution to the study of narratology. Watts contends that a story must pass through 8 discrete plot points:

- Stasis: The everyday life of the protagonist, which becomes disrupted by the story’s inciting incident, or “trigger.”

- Trigger: Something beyond the protagonist’s control sets the story’s conflict in motion.

- The quest: Akin to the rising action, the quest is the protagonist’s journey to contend with the story’s conflict.

- Surprise: Unexpected but plausible moments during the quest that complicate the protagonist’s journey. A surprise might be an obstacle, complication, confusion, or internal flaw that the protagonist didn’t predict.

- Critical choice: Eventually, the protagonist must make a complicated, life-altering decision. This decision will reveal the protagonist’s true character, and it will also radically alter the events of the story.

- Climax: The result of the protagonist’s critical choice, the climax determines the consequences of that choice. It is the apex of tension in the story.

- Reversal: This is the protagonist’s reaction to the climax. Reversal should alter the protagonist’s status, whether that status is their place in society, their outlook on life, or their own death.

- Resolution: The return to a new stasis, in which a new life goes forth from the ashes of the story’s conflict and climax.

If the plot of a story passes through each of these moments in order, the author has built a complete narrative.

Watts expands upon this plot structure in his book Write a Novel and Get It Published.

Plot Structures: Save the Cat

The Save the Cat plot structure was developed by screenwriter Blake Snyder. Although it primarily deals with screenplays, it maps out story structure in such a detailed way that its many elements can be incorporated into all types of stories.

Rather than reinvent the wheel, we’ll point you to the great breakdown of Save the Cat, including a worksheet you can use to draft your own story. Find it here, at Reedsy.

Plot Structures: The Hero’s Journey

The Hero’s Journey is a plot structure originally crafted by Joseph Campbell. Campbell argued that the plot of a story has three main acts, with each act corresponding to the necessary journey a hero must undergo in order to be the hero.

Those three parts are: Stage 1) The Departure Act (the hero leaves their everyday life); Stage 2) The Initiation Act (the hero undergoes various conflicts in an unknown land); and Stage 3) The Return Act (the hero returns, radically altered, to their original home).

In his screenwriting textbook The Writer’s Journey, Christopher Vogler expands these three stages into a 12 step process. To Vogler, the hero’s journey must pass through these parts:

The Departure Act

- The Ordinary World: We meet our hero in their mundane, everyday reality.

- Call to Adventure: The hero is confronted with a challenge which, if they accept it, forces them to leave their ordinary world.

- Refusing the Call: Recognizing the dangers of adventure, the hero will, if not reject the call, at least demure or hesitate while considering the many probable ways it will go wrong.

- Meeting the Mentor: The hero decides to go on the adventure, but they are much too inexperienced to survive. A mentor accompanies the hero to help them be smart and strong enough for the journey.

The Initiation Act

- Crossing the Threshold: By leaving for their adventure, the hero crosses a liminal threshold. They cannot go back, and if they return home, they won’t return the same.

- Tests, Allies, and Enemies: The hero enters a strange new world, with unfamiliar rules and dangers. They also encounter allies and enemies that broaden and complicate the story’s conflicts.

- Approach (to the Inmost Cave): The “inmost cave” is the locus of the journey’s worst dangers—think of the dragon’s lair in Beowulf or the White Witch’s castle in The Chronicles of Narnia. The hero is approaching this cave, though must locate it and build strength.

- Ordeal: This is the hero’s biggest test (thus far). Sometimes the climax (but not always), the ordeal forces the hero to face their biggest fears, and it often occurs when the hero receives unexpected news. This is a low point for the hero.

- Reward: The hero receives whatever reward they gain from their ordeal, whether that reward is a material possession, greater knowledge, someone’s freedom, or the resolution of the hero’s internal conflict.

The Return Act

- The Road Back: The hero ventures back home, though their newfound reward raises additional dangers, many of which stem from the Inmost Cave.

- Resurrection: The main antagonist returns for one final fight against the hero. This is a test of whether the hero has truly learned their lesson and undergone significant character development; it is also the other climax of the story. The hero comes closest to death here (if they don’t actually die).

- The Return: The elixir is whatever reward the hero accrued, whether that be knowledge or material wealth. Regardless, the hero returns home a changed person, and their return home highlights the many ways in which the hero has changed—both for better and worse.

Plot Structures: Fichtean Curve

The Fichtean Curve was originally crafted for pulp and mystery stories, though it can certainly apply to stories in other genres. Described extensively by John Gardner in The Art of Fiction, the Fichtean Curve argues that a story plot has three parts: a rising action, a climax, and a falling action.

In the Fichtean Curve, the rising action comprises about ⅔ of the entire story. Moreover, the rising action isn’t linear. Rather, a series of escalating and de-escalating conflicts slowly pushes the story towards its climax.

If you’ve ever read one of Agatha Christie’s murder mysteries, then you’re already familiar with the Fichtean Curve. In Murder on the Orient Express, for example, Hercule Poirot continues to stoke the flames of the story’s many suspects: he uncovers every passenger’s flaws, insecurities, and secrets, each time generating a little more conflict, and each time narrowing down the murderer until the story’s explosive climax.

What is Plot Without Conflict?

In a moment, we’ll look at some common plot devices that authors use to keep their stories fresh and engaging. But first, let’s discuss a central element of all plots: conflict. Is it always essential to good storytelling? What is plot without conflict?

First, let’s define conflict. Conflict is not necessarily two characters bickering, although that’s certainly an example. Conflict refers to the opposing forces acting against a character’s goals and interests. Sometimes, that conflict is external: an enemy, bureaucracy, society, etc. Other times, the conflict is internal: traumas, illogical ways of thinking, character flaws, etc.

Typically, conflict is the engine of the story. It’s what incites the inciting incident. It’s what keeps the rising action rising. The climax is the final product of the conflict, and the denouement decides the outcome of that conflict. The plot of a story relies on conflict to keep the pages turning.

So, a word of advice: if you’re developing a story plot, but don’t know where to go, always return to conflict. Each scene should stoke a conflict forward, even if the conflict isn’t readily apparent just yet. Anything that doesn’t explore, expand, or resolve the elements of a story’s conflict is likely wasting the reader’s time.

If you’re developing a story plot, but don’t know where to go, always return to conflict.

Before we move on, it’s worth noting that the centrality of conflict in plot in literature is a very Western notion. Some forms of storytelling don’t rely on conflict. The Eastern story structure Kishōtenketsu, for example, involves characters reacting to random external situations, rather than generating and resolving their own conflicts. A conflict might be featured in this kind of storytelling, but the story engine is the characters themselves, their own complexities and dilemmas, and how they survive in a world they can’t control.

To learn more about conflict in story plot, check out our article:

Common Plot Devices

The plot of a story is influenced by many factors. While plot structures give the framework for the story itself, the author must employ plot devices to keep the story moving, otherwise the rising action will never become a climax.

These plot devices ensure that your reader will keep reading, and that your story will deepen and complicate the themes it seeks to engage.

Aristotle’s Plot Devices

In Poetics, Aristotle describes three plot devices which are essential to most stories. These are:

1. Anagnorisis (Recognition)

Luke, I am your father! Anagnorisis is the moment in which the protagonist goes from ignorance to knowledge. Often preceding the story’s climax, anagnorisis is the key piece of information that propels the protagonist into resolving the story’s conflict.

2. Pathos (Suffering)

Aristotle defines pathos as “a destructive or painful action.” This can be physical pain, such as death or severe wounds, but it can also be an emotional or existential pain. Regardless, Aristotle contends that all stories confront extreme pain, and that this pain is essential for the propulsion of the plot. (This is different from the rhetorical device “pathos,” in which a rhetorician seeks to appeal to the audience’s emotions.)

3. Peripeteia (Reversal)

A peripeteia is a moment in which bad fortunes change to good, or good fortunes change to bad. In other words, this is a reversal of the situation. Often accompanied by anagnorisis, peripeteia is often the outcome of the story’s climax, since the climax decides whether the protagonist’s story ends in comedy or tragedy.

Plot Devices for Story Structure

The plot of a story will gain structure from the use of these devices.

Backstory

Backstory refers to important moments that have occurred prior to the main story. They happen before the story’s exposition, and while they sometimes change the direction of the story, they more often provide historical parallels and key bits of characterization. Sometimes, a story will refer to its own backstory via flashback.

Deus Ex Machina

A deus ex machina occurs when the protagonist’s fate is changed due to circumstances outside of their control. The Gods may intervene, the antagonist may suddenly perish, or the story’s conflict resolves itself. Generally, deus ex machina is viewed as a “cop out” that prevents the protagonist from experiencing the full growth necessary to complete their journey. However, this risky device may pay off, especially in works of comedy or absurdism.

In Media Res

From the Latin “in the middle of things,” a story is “in media res” when it starts in the middle. On Page 1, word 1, the story starts somewhere in the middle of the rising action, hooking the reader in despite the lack of context. Eventually, the story will properly introduce the characters and take us to the beginning of the conflict, but “in media res” is one way to generate immediate interest in the story.

Plot Voucher

A plot voucher is something that is given to the protagonist for later use, except the protagonist doesn’t know yet that they will use it. That “something” might be an item, a piece of information, or even a future allegiance with another person. Many times, a plot voucher is bequeathed before the story’s conflict properly takes shape. For example, in the Harry Potter series, the Resurrection Stone is hidden in Harry’s first golden snitch, making the snitch a plot voucher.

Plot Devices for Complicating the Story

What is the plot of a story, if not complicated? These plot devices bring your readers in for a wild ride.

Cliffhanger

A cliffhanger occurs when the story ends before the climax is resolved. Specifically, the story ends mid-climax so that the reader experiences the height of the story’s tension, but doesn’t see the outcome of the climax and the fate of the protagonist or conflict. Cliffhangers will generally occur when the story is part of a series, though it can also have literary merit. In One Thousand and One Nights, Scheherazade ends her stories on cliffhangers so that the king keeps postponing her execution.

MacGuffin

A MacGuffin is a plot device in which the protagonist’s main desire lacks intrinsic value. In other words, the protagonist desires the MacGuffin, which causes the story’s conflict, but the MacGuffin itself is actually valueless. Many times, the protagonist doesn’t even obtain the MacGuffin, because they have learned what lessons they were supposed to learn from the chase. An example is the falcon statuette in The Maltese Falcon. This statuette is never obtained, but it drives the novel’s many murders and double crossings.

Red Herring

A red herring is a distraction device in which the author misleads the reader (or other characters) with seemingly-relevant details. (The MacGuffin is a form of red herring.) Red herrings are primarily found in mystery and suspense stories, as they string the reader down different possibilities while distracting from the truth. Although this plot device can complicate the story and even build symbolism, it can also fracture the reader’s trust in the author, so writers should use it sparingly and wisely. (This is slightly different from the logical fallacy “red herring,” in which irrelevant information is used to distract the reader from a faulty argument.)

For more plot devices and storytelling techniques, take a look at our article The Art of Storytelling.

https://writers.com/the-art-of-storytelling

8 Types of Plot in Literature

Certain types of plot recur throughout literature, especially in genre fiction. These stories build upon the previously mentioned plot devices, and they have their own tropes and archetypes which the author must fill to tell a complete story.

Some, but not all, of the following plots were originally defined by Christopher Booker in his work The Seven Basic Plots. (We’ve omitted some of the plots he mentions if they are rarely seen in contemporary literature.)

The plot of a story might take the following shapes:

1. Plot of a Story: Quest

Often resembling the Hero’s Journey, a quest is a story in which the protagonist sets out from their homeland in search of something. They might be searching for treasure, for love, for the truth, for a new home, or for the solution to a problem. Often accompanied by other allies, and often embarking on this journey with hesitation, the protagonist comes back from their quest stronger, smarter, and irreversibly changed—if they make it back alive.

Examples of the quest include: The Lord of the Rings by J. R. R. Tolkien, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and The Harry Potter Series.

2. Plot of a Story: Tragedy

A tragedy is a story of a well-meaning protagonist who, due to their flaws or shortcomings, fails to resolve the story’s conflict. (The hero’s tragic flaw is known as hamartia.) Tragedies often highlight the terrible circumstances that the protagonist finds themselves in, or the impossible moral quandaries that they must resolve (but don’t). Readers come to love the tragic hero both despite and because of their flaws, and their inability to resolve the conflict often comes as a great moral or personal loss, even resulting in the protagonist’s death.

Examples of the tragedy include: Romeo & Juliet by Shakespeare, The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, Oedipus Rex by Sophocles, Frankenstein by Mary Shelley, Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck, and Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë.

3. Plot of a Story: Rags to Riches

A rags to riches story involves a protagonist who goes from dire poverty to excessive wealth. In addition to navigating issues of class and identity, these stories often showcase the protagonist’s inner world as they adjust to drastically new life circumstances. The plot of a rags to riches story will follow the protagonist’s relationship to wealth, and the things that protagonist chases precisely because of that wealth.

Examples of the rags to riches include: Great Expectations by Charles Dickens, The Count of Monte Cristo Alexandre Dumas, and Q & A by Vikas Swarup.

4. Plot of a Story: Story Within a Story

The story within a story, also known as an embedded narrative, one of the less-structured types of plot. Essentially, the author embeds a second story, complete with its own narrative and conflict, to bolster the progression of the main story. Embedded narratives often reflect the themes of the main narratives, but they can also complicate and challenge those themes, providing additional layers of meaning to the story. This is not to be confused with parallel plot, because the story within a story is an invention solely for the sake of advancing the main narrative, whereas a parallel plot has multiple, equally important narratives.

Examples of the story within a story include: The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky, Hamlet by Shakespeare, Moby-Dick by Herman Melville, Afterworlds by Scott Westerfeld, and Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes.

5. Plot of a Story: Parallel Plot

A parallel plot is a story in which two or more concurrent plots are told side-by-side. Each plot influences the course of the other plot, even if those stories happen on opposite ends of the world. Every narrative that occurs in a parallel plot is equally vital to the story as a whole.

Examples of parallel plot include: Kafka on the Shore by Haruki Murakami, A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens, Break the Bodies, Haunt the Bones by Micah Dean Hicks, The Testaments by Margaret Atwood, and In the Time of the Butterflies by Julia Alvarez.

6. Plot of a Story: Rebellion Against “The One”

A story of rebellion follows a hero who actively resists the oppressive force of an omnipotent antagonist. Despite working tirelessly to defeat that antagonist, the protagonist is ill-equipped to do so as a singular and powerless entity. So, the story often ends with the protagonist submitting to the antagonist, or else perishing altogether.

Examples of rebellion against “The One” include: 1984 by George Orwell, The Hunger Games Series by Suzanne Collins, “Harrison Bergeron” by Kurt Vonnegut, and The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood.

7. Plot of a Story: Anticlimax

The anticlimax is a story that details the falling action after a climax has already occurred. In other words, the anticlimax does not have a climax itself: the climax is merely provided as backstory, and the novel is dedicated to the events of the story’s denouement. This not to be confused with the plot device anticlimax, which describes a story’s resolution that is actually incredibly simple.

Examples of the anticlimax include: The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner, Encircling by Carl Frode Tiller, and Oryx & Crake by Margaret Atwood.

8. Plot of a Story: Voyage and Return

Stories of voyage and return involve protagonists who journey into strange worlds. Often, a story of “Quest” is also a story of voyage and return, but not always. For the protagonist to return home from their voyage, they must achieve some sort of daring act that resolves the story’s conflict, such as finding treasure or vanquishing an antagonist. Both the voyage and the return teaches the protagonist life lessons and pushes them to make difficult decisions.

Examples of voyage and return include: The Iliad and the Odyssey by Homer, Coraline by Neil Gaiman, The Lord of the Flies by William Golding, Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift, Candide by Voltaire, and The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum.

Plot-Driven vs. Character-Driven Stories

A common distinction between different types of fiction is whether the story is “plot driven” or “character driven.” This refers to whether the plot of a story defines the characters, or whether the characters define the plot of a story.

Specifically, this distinction is made to differentiate literary fiction vs. genre fiction. Generally, a piece of literary fiction will have the characters in control of the plot, as the story’s plot points are built entirely off of the decisions that those characters make and the influences of those characters’ personalities.

Genre fiction, by contract, tends to have predefined plot structures and archetypes, and the characters must fit into those structures in order to tell a complete story.

While this general distinction helps organize the qualities of fiction, don’t treat them as absolutes. Literary fiction borrows plot devices from genre fiction all the time, and there are many examples of genre fiction that are character driven. Your story should build a working relationship between the characters and the plot, as both are essential elements of the storyteller’s toolkit.

Your story should build a working relationship between the characters and the plot, as both are essential elements of the storyteller’s toolkit.

Plot vs. Story

Finally, what is the difference between plot vs. story? The two terms are often used interchangeably, and indeed, something that affects the plot will usually affect the story. But, the two do not share the same precise definitions.

Plot definition: The story’s series of events. Think of plot as the story’s skeleton: it defines the What, When, and Where of the story, which allows for everything else (like characters and themes) to develop. What happens (and what is the cause-and-effect), when does it happen, and where is it happening?

Story definition: The entirety of the work, including its conflicts, themes, and messages. In addition to plot, the story answers questions of Who, Why, and How. Who is involved (and who are they psychologically), why does this conflict happen, and how do the characters resolve the conflict?

To learn more about writing a cogent story from a compelling plot, read our article on the topic.

https://writers.com/stories-vs-situations-how-to-know-your-story-will-work-in-any-genre

Plot vs. Story Venn Diagram

The differences between plot vs. story are summarized in the following Venn Diagram.

Explore the Plot of a Story at Writers.com

There are two types of storytellers: plotters and pantsers. A pantser “writes by the seat of their pants,” making snap decisions about the story’s events on the spot. Plotters map out everything in advance, setting up the plot of a story before setting down the first word.

Whether you’re a plotter, a pantser, or anything in between, the courses at Writers.com can help! Plot your novel or simply write it in any of our upcoming writing classes.

Excellent summary of a very overwhelming and confusing subject!

Thank you for the excellent help on plot. Although I’ve written for many years, I learned some good stuff which I will use!

Happy Holidays,

Dave Beaty

[…] What is the Plot of a Story? […]

I am so delighted to see that my late husband, Nigel Watts PhD’s work is still in the world and being referenced 22 years after his death. Some of his novels are still available on Amazon, including the republished Twenty Twenty, published in 1995, predicting a global pandemic and warnings of climate catastrophe. But ‘Writing a Novel and Getting it Published’ is the longest in print book of his work. I’m so proud and pleased that he continues to help writers. Writing was his passion, vocation and career.

This is really helpful. Thanks, Sean!

This was really well done! Thank you. Cor